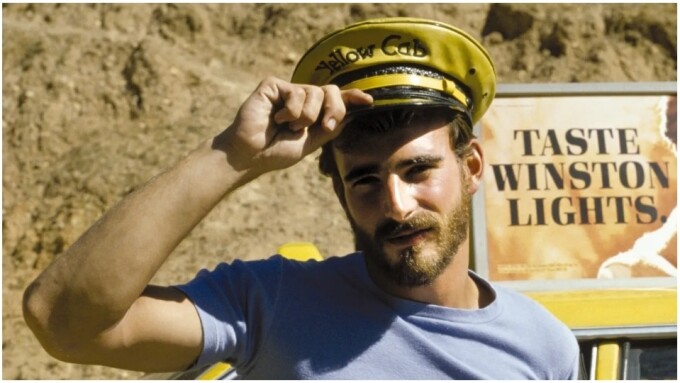

LOS ANGELES — The enduring influence of erotic icon Al Parker on men's style across several generations is explored in a new essay recently published by GQ.com.

The piece, by Nathan Tavares, is titled "How the '70s 'Clone' Look Paved the Way for the Queer Clothing of Today."

"Every historical social scene has had its uniform. But when one particular look cropped up in the post-Stonewall gay scene of the 1970s, it was so popular — and so distinct — that the guys who sported it were dismissed as 'clones,'" Tavares writes. "Inspired by archetypes like cowboys and bikers, the clone look was all about denim, plaid shirts, bomber jackets, and t-shirts, with a body-conscious bent. Like the Marlboro Man... if he happened to be into other Marlboro Men."

The "clone" look was born "in the hyper-stylized worlds of porn centerfolds from prolific companies like COLT Studio, but quickly emerged into the real world," notes Tavares. "And while the nickname was initially pejorative, the clone period marked perhaps the first time that gay men presented themselves with a queer-signaling uniform that was a direct response to societal stereotypes. You can draw a direct line from the clones of yesteryear to Lil Nas X’s wild red carpet fits, along with much of the output of the latest generation of queer designers."

Tavares explains how other fashion influences at the time invited men to "embrace more feminine and playful styles," and popular culture such as "The Producers" exploited "gay minstrel stereotypes," the clone look veered sharply in a different direction by "taking traditional masculinity and queering the hell out of it."

"While it’s not so easy to pinpoint precisely who originated the clone ideal, guys who were alive at the time usually bring up Al Parker," Tavares states, noting that a biography by Roger Edmondson "points to him as one of the founding daddies of the style."

"When magazines like Stallion featured titans with cannonball biceps and granite slabs of pecs, Parker offered a comparatively slimmer build, sheathed in denim and with a neat beard that played to working-class fantasies," adds the writer. "He became one of the biggest stars in that golden era of pornography, eventually starring in about 21 films. Decades before sex workers began taking to OnlyFans to control their own careers, Parker founded his own production company, Surge Studio, with his late partner, after COLT refused to give him a share of the profits of movies he starred in."

Tavares quotes Ben Barry, the dean of the school of fashion at the New School’s Parsons School of Design, who observed how "(t)he clone look was certainly about a white gay man’s response and engagement with those archetypes... The whiteness and the body-consciousness of it in terms of which bodies didn’t have the same privilege to wear it is an important element to highlight."

Designer James Flemons "often works Americana staples like tanks and trucker jackets into his gender-neutral eclectic basics brand, Phlemuns," Tavares writes. "He styled many of Lil Nas X’s early looks, including the 2019 Time cover that featured the singer in a red cowboy-inspired getup. Further proof that the clone isn’t dead: Lil Nas X’s 'Montero (Call Me By Your Name)' video features an army of denim-clad doubles of the singer, along with the lyric 'I wanna fuck the ones I envy' — which could be a pretty great clone motto."

Find the complete essay at GQ.com.

Image source: FalconStudios.com