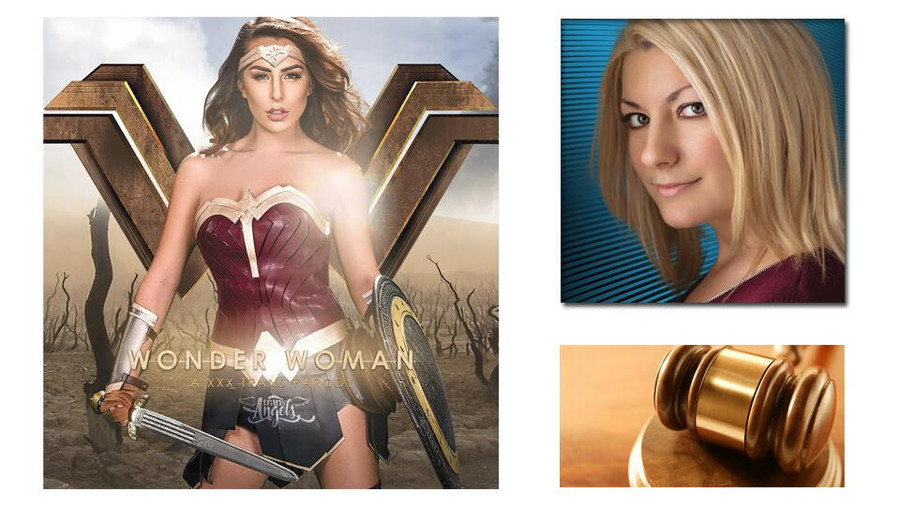

Legendary internet “Rule 34” declares that “if it exists, there is porn of it — no exceptions.” This includes the loads of movies, books and TV shows, among other things, for which porn parodies have been made. The statement made by Rule 34 is pretty clear cut, however, the legality of such works is not.

Copyright protects creative works, such as movies, photos, books and songs. The owner of a copyrighted work has the exclusive rights to (1) reproduce (i.e. copy) the work, (2) prepare derivative works (i.e. modified versions of the work), (3) distribute copies of the work to the public and (4) perform or display the work publicly. Generally, the duration of protection for works created on or after January 1, 1978, is the lifetime of the author plus 70 years, or in some cases where the author is anonymous, 95 or 120 years, depending on certain factors. In other words, it’s a really long time!

If you want a happy ending for your porn parody, make sure you know the applicable laws, so you can best craft your narrative and imagery to avoid infringement issues.

A copyright provides the owner with the right to prevent others from copying the covered work — usually. The operative word here is “usually,” as some exceptions exist, the main one being “fair use.” The doctrine of fair use allows a third party to exercise one or more rights of the copyright holder under particular conditions, such as to parody the original. The fair use defense to copyright infringement is a balance between encouraging people to create (by giving them exclusivity to their creations through copyright protection) with the free speech rights of others (to comment, learn, criticize and report news, etc.).

Courts weigh four factors when determining whether a particular use of another’s work is a “fair use.” The first factor evaluates “the purpose and character of the use.” This requires a determination of whether the use is for commercial gain or nonprofit (e.g., educational) endeavors. The fact that a work is for commercial gain does not automatically remove it from the umbrella of fair use, but a non-profit purpose does more strongly tip the scale in favor of fair use. The second factor assesses “the nature of the copyrighted work.” Here, there is an examination of the type of work which has been taken. For example, a copying of facts is more likely a fair use than a copying of fiction, since dissemination of facts is considered a desirable benefit to the public. The third factor measures “the amount and substantiality of the portion taken.” A copying of a small percentage of a work is more likely a fair use than a verbatim copying of the entirety. Finally, the fourth factor weighs “the effect of the use upon the potential market.” If a work “supersedes” the original work by making it unnecessary to purchase the original, that will lean towards a lack of fair use.

Creating a pornographic version of another’s work does not automatically qualify as “parody” fair use. In the 1981 case of MCA, Inc. v. Wilson, the U.S. Second Circuit Court affirmed that the defendants’ performance of the song “Cunnilingus Champion of Company C” was not fair use, and instead infringed the plaintiffs’ copyright in the song “Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy.” The court stated that “[w]e are not prepared to hold that a commercial composer can plagiarize a competitor’s copyrighted song, substitute dirty lyrics of his own, perform it for commercial gain and then escape liability by calling the end result a parody or satire on the mores of society.”

According to the 1994 landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision of Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., parody is the “…use of some elements of a prior author’s composition to create a new one that, at least in part, comments on that author’s works.” The theory is that parody can provide social benefit, “by shedding light on an earlier work, and, in the process, creating a new one.” It is this “transformative” nature — creating something new that is intellectually or artistically beneficial to society from something existing — which heavily favors a finding of fair use.

Along those lines, in Fifty Shades Limited et al. v. Smash Pictures Inc. et al. brought in the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California, the defendant who had made a film, “Fifty Shades of Grey: A XXX Adaptation,” settled a copyright infringement lawsuit in 2013 instead of fighting back. An executive with Smash had reportedly described the work as “…a XXX adaption which will stay very true to the book and its S&M-themed romance.” This would not have bode well in court where a parody must transform a work into something new rather than be a “knock off,” so to speak.

On the other hand, in the 1981 case of Pillsbury Co. v. Milky Way Productions, Inc., an image published in “Screw” magazine portraying the Pillsbury Doughboy character in sexual acts, when challenged as a copyright infringement, was found to be fair use. The U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Georgia determined that the use “…is more in the nature of an editorial or social commentary than it is an attempt to capitalize financially on the plaintiff’s original work. Although the portrayal is offensive to the court, the court has no doubt that Milky Way intended to make an editorial comment on the values epitomized by these trade characters.” The court observed that the plaintiff failed to introduce more than a “sliver of evidence” showing economic harm, and consequently, refused to fill the void by presuming such harm.

In 2002, in Lucasfilm Ltd. v. Media Market Group, Ltd., the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California dismissed a motion for preliminary injunction against the sale of an animated porn parody called “Starballz.” The court explained that “‘Starballz’ is a parody of Star Wars, in that it is a ‘literary or artistic work that broadly mimics an author’s characteristic style and holds it up to ridicule.’” The court pointed to the Campbell case, explaining “[t]he Supreme Court has stated that for the purposes of copyright law, ‘the heart of any parodist’s claim to quote from existing material is the use of some elements of a prior author’s composition to create a new one that, at least in part, comments on that author’s works.’” The court indicated that the parodic nature of “Starballz” may be fair use.

The evaluation of whether a use is fair is made on a case-by-case basis. Throughout past case decisions, though, you see the continual notion of a balancing act between rights of the author and free speech rights of the public. In the 1978 case of Walt Disney Productions v. Air Pirates, the use of seventeen Walt Disney cartoon characters in a comic book that depicted Mickey Mouse and the other Disney characters involved in sex and drugs was held not to be fair. The U.S. Ninth Circuit Court found that the amount of the portion copied exceeded permissible levels, noting that, “[w]hen persons are parodying a copyrighted work, the constraints of the existing precedent do not permit them to take as much of a component part as they need to make the ‘best parody.’ Instead, their desire to make the ‘best parody’ is balanced against the rights of the copyright owner in his original expressions.”

The determination of whether a use is fair is subjective, which means that the expected outcomes of litigation are typically uncertain. There is no bright line separating legal fair uses from illegal infringements. In addition, this article covers copyright fair use — trademark fair use, although related, is a different analysis, which we’ll save for another day. In the meantime, you’ll need to understand it when you parody a brand or title in addition to, or instead of, creative content. The moral of this story is that if you want a happy ending for your porn parody, make sure you know the applicable laws so you can best craft your narrative and imagery to avoid infringement issues.

Disclaimer: The content of this article constitutes general information, and is not legal advice. If you would like legal advice from Maxine Lynn, an attorney-client relationship must be formed by signing a letter of engagement with her law firm. To inquire, visit Sextech.Lawyer.

Maxine Lynn is an intellectual property (IP) attorney with the law firm of Keohane & D’Alessandro, PLLC, having offices in Albany, New York. She focuses her practice on prosecution of patents for technology, trademarks for business brands, and copyrights for creative materials. Through her company, Unzipped Media, Inc., she publishes the Unzipped Sex, Tech & the Law® blog at SexTechLaw.com.