What do the Florida Keys, Pee-Wee Herman and a crucifix-shaped dildo all have in common? Well, for starters, they’re three rather intriguing reasons to finish at least one book this year.

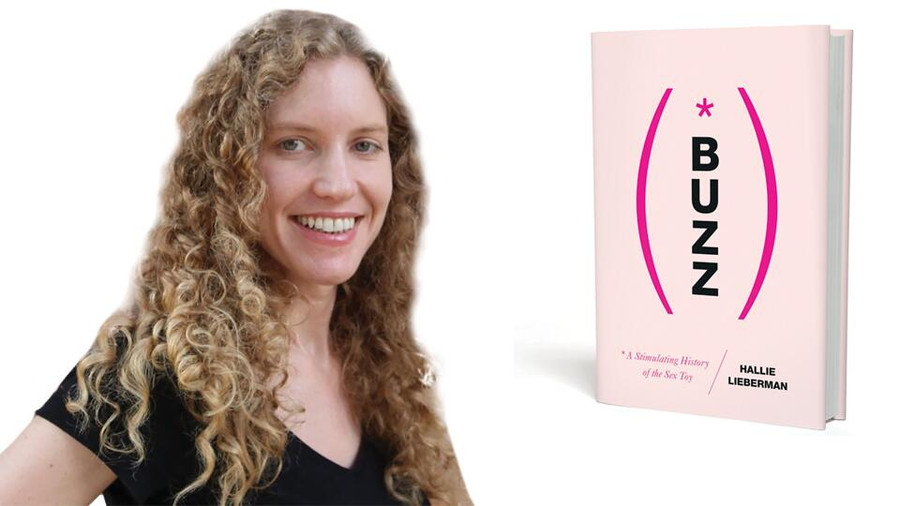

“Buzz: A Stimulating History of the Sex Toy” is author - Hallie Lieberman’s non-fiction debut, and this Southern-bred Ph.D. might never have penned one of 2018’s most talked-about accounts of sex toy history without a teenhood chocked full of masturbatory misadventures.

I read one business report saying that the sex-toy industry had reached maturity, but I’m not sure if that’s true or not. I think there’s a lot of room for growth.

“When I was in high school, mentioning I masturbated caused people to freak out and make assumptions, like I must be lonely or that I never wanted to be in a relationship,” says Lieberman. “That idea of a woman taking control of her sexuality, giving herself pleasure, it freaked people out, which interested me.”

“Buzz” is a full-bodied history of the sex toy, starting with the stone-carved dildos of the literal caveman days, and its recent release has often been compared — positively — to Lynn Comella’s pleasure industry retrospective “Vibrator Nation.” The New York Times pitches “Buzz” and “Vibrator Nation” as timely, almost sister-esque pieces, with Lieberman’s take on the sex toy timeline as more of an all-encompassing overview in contrast to Comella’s feminist-focused lens.

“Sex toys soaked up the meanings of whoever was promoting them,” writes Liberman in an excerpt from Buzz. “In one context, they embodied liberationist radical feminist values, while in another, they symbolized traditional gender and sexual roles. Feminists championed them for masturbation while traditionalists promoted them for monogamous heterosexual sex. Sex toys symbolized gay liberation in The Pleasure Chest, and disability rights in Gosnell Duncan’s newly renamed company Scorpio Products.”

Growing up in the All-American purity of Sarasota, Fla., Lieberman’s youth was bombarded with random encounters of the orgasmic kind, hence the rather curious inspirations that eventually lead to her Master’s dissertation on the history of sex in the U.S.

“Around age 10, I found a vibrator in a Florida Keys hotel room drawer and my mom was so upset that I was touching it,” recalls Lieberman. “I saw that sex toys were very powerful objects, and I was fascinated by them.”

Later, Lieberman would find an unlikely hero in infamous actor Paul Reubens of the Pee-Wee Herman children’s television series. This well-known tale, a nightmare of every suburban parent, took place near Lieberman’s hometown in a porn theater, where Reubens was ultimately arrested for a perfectly natural act in a place that seemed otherwise appropriate for self-pleasure.

Even as a youngster, Lieberman says she couldn’t understand the connection between sexuality and societal taboos.

“I was a kid, a big fan, and I was so upset that he had to end his show because he masturbated,” says Lieberman. “I didn’t know why people were so scandalized by a sexual practice that doesn’t hurt anybody else, and that only involves the self.”

Cut to Lieberman’s discovery of Divine Interventions, a sex toy company famous for turning religious symbols, like a crucified Christ, into insertable objects, and this future academic was officially hooked on the history, politics and power of pleasure.

After three successful stints on college campuses across the U.S. — University of Florida for undergrad, then the University of Texas-Austin for her Master’s, and finally the University of Wisconsin-Madison – Lieberman had done her fair share of historical and modern research, and finally graduated from the Land of Dairy and Football with her Ph.D. These notoriously conservative environments provided just the right amount of push-back to fuel Lieberman’s quest to de-mystify the stigma of sex toys.

While in grad school in Austin, Lieberman found that even behind closed doors, much of sexual discourse was still silenced.

“I began working for home-party company Passion Parties and it was 2004, when selling sex toys was still illegal in Texas,” Lieberman recalls. “I had to use all these euphemisms when selling them. I had to call vibrators massagers, and I couldn’t mention the clitoris. I was supposed to say ‘man in the boat.’ It was crazy!”

After beginning the research that would eventually form the foundation of “Buzz” around 2008, Lieberman realized that pleasure history was not only in need of a modernized approach, but lot of myth-busting as well. Remember that oldie but goodie about 1800s doctors treating “female hysteria” with the world’s first vibrators? It’s a big, fat lie, according to the textbooks.

“I checked all the sources and found no evidence that this ever happened,” says Lieberman. “So I realized there needed to be a more definitive account.”

Lieberman’s research took her across the country and into the homes of some of the pleasure industry’s most-respected pioneers. She interviewed household names like Dell Williams and Joani Blank, who opened some of the first feminist sex toy shops during the hey-day of the Summer of Love, both of whom were as fiery as ever in their senior years.

“They were so passionate about educating women about their sexuality and teaching women how to give themselves orgasms. They were real pioneers in the 1970s,” recalls Lieberman.

“Dell was still sassy in her 90s. I mean I was interviewing her in a Trump Tower in N.Y. where she lived. She was in a wheelchair in the lobby and speaking really loudly about her erotic dreams and talking about how she sold ‘an orgasm a day keeps the doctor away’ pins. She wasn’t embarrassed or ashamed at all,” says Lieberman. “I talked to Joani in her townhouse in Oakland, Calif., which had awesome erotic art on the walls. She was 77, single and still interested in dating.”

What decidedly shocked Lieberman wasn’t a couple of swinging seniors with a still-burning passion for sex. Although we often view the past as a time capsule of forced frigidity for females, magazines and newspapers were a lot more open-minded to precarious advertising just a few decades ago.

“In some ways we were more liberated in the 19th and early 20th century when it came to sex toys because they were openly advertised in mainstream media, albeit as health devices and home appliances,” says Lieberman.

The likes of the Chicago Tribune and New York Times openly advertised vibrators under the guise of back massagers, and drug stores carried rectal dilators — which, unsurprisingly, look just like modern butt plugs — as a supposed cure for everything from asthma to constipation.

“Now when we are open about what these devices are used for, they are less visible in mainstream culture,” explains Lieberman.

After exploring the depths and shallows of our life-long obsession with copulation and onanism, what’s next, according to our historical hostess?

“I see two trajectories: one towards handmade low-tech toys, the kind of hipster toys like [indie manufacturer] Hole Punch, and a trajectory towards super high-tech: sex robots, VR, teledildonics,” muses Lieberman. “I read one business report saying that the sex-toy industry had reached maturity, but I’m not sure if that’s true or not. I think there’s a lot of room for growth.”