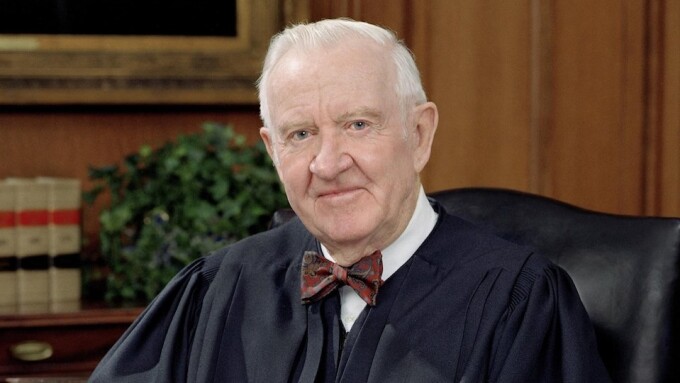

WASHINGTON, D.C. — Retired Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens, who led the Court majority that upheld online freedom of speech in the mid 1990s when Congress attempted to establish government censorship of “obscene” material, has died at 99.

Stevens, a World War II veteran appointed by Republican President Gerald Ford, became recognized as an unlikely champion of liberal causes during his time on the Supreme Court (1975-2010). His opinions crucially shaped the direction of the Internet.

In 1992, years before most Americans could conceive of anything like Amazon.com — or even having the Internet at home — as anything but sci-fi, Stevens authored the opinion that online retailers should not be required to collect taxes on out-of-state sales, paving the way for the unstoppable growth of online commerce.

Then, in 1997, Stevens authored the opinion that resulted in the protection of sexually explicit material on the Internet.

After Congress enacted a broad censorship law, prudishly named the Communications Decency Act (CDA), making it a federal crime to post "indecent" material on public websites that could be accessed by minors, Stevens wrote an opinion upholding the most basic principles of free speech.

“If upheld,” as CNet’s Declan McCullagh explained in a 2010 article celebrating Stevens’ legacy upon his retirement, “the CDA would have levied broadcast-style regulations on the internet, making it a felony for even a news organization to post certain four-letter expletives of the sort that landed the late comedian George Carlin in trouble with the Federal Communications Commission. The Internet would have been left heavily censored, while DVDs, magazines, newspapers, and satellite radio, and TV were not.”

“Online porn,” continues McCullagh, would have been completely forbidden — unless, that is, “every single salacious image or video stayed behind a pay wall requiring credit card verification for proof of age.”

As CNet speculated, “if the CDA had remained in effect, the Internet porn industry may have moved offshore instead of being headquartered in California's San Fernando Valley.”

Stevens was far-seeing in his vision of digital freedom of expression. “The record demonstrates that the growth of the Internet has been and continues to be phenomenal,” he wrote. “As a matter of constitutional tradition, in the absence of evidence to the contrary, we presume that governmental regulation of the content of speech is more likely to interfere with the free exchange of ideas than to encourage it. The interest in encouraging freedom of expression in a democratic society outweighs any theoretical but unproven benefit of censorship.”

With the current Supreme Court packed with religiously motivated ideologues like Justices Thomas, Alito, Gorsuch and Kavanaugh, Stevens’ cautious take on freedom of expression seems like a relic of a much quainter era, when the Internet was seen as a new frontier of knowledge and information rather than a battlefield of contention and deceit in need of governmental oversight.